Different people play computer games for very different reasons. Some play for fun, some play to win, and some play to let off steam. I play video games for a chance to briefly disconnect from this world and transcend to another, perhaps totally different one. Given this, you can guess that atmosphere and immersion into that other digital universe are crucial factors I look for in a video game. Crucial, but not the only ones, since there are many elements from which a gaming masterpiece is assembled: for instance, graphics or art, music, sound effects, story, and many others.

When I got two games I had previously never heard of, Limbo and Inside from a developer called “Playdead“, for just a couple of bucks in a Steam sale, I never imagined that these little gems would excel in most of the aspects that differentiate a regular game from a masterpiece.

Limbo

Chronologically, Limbo came first of the two games, published in July 2010. Its completely monochromatic style reminded me of film noir (in its color palette and film grain effect) and German expressionism (with apparently simple shapes that tell a complex story or turn out to be complex themselves). In the game, the player controls an anonymous and faceless boy through numerous perilous environments and encounters with dangerous creatures in pursuit of finding his sister. He advances through the game by completing various puzzles designed to teach the player how to solve them after numerous failed attempts (that often lead to the boy’s demise).

Playdead called this game mechanic “trial and death,” stating that they used gruesome depictions of the boy’s deaths to make players think twice (and harder) before making their next attempt. Interested parties made serious attempts to influence the developer to water down the horror elements of the game or to make it more acceptable, but Playdead continued with their original vision. The ending, which is the most criticized part of the game, in my opinion does justice to the whole experience. Limbo, it seems, just doesn’t deserve to end.

Inside

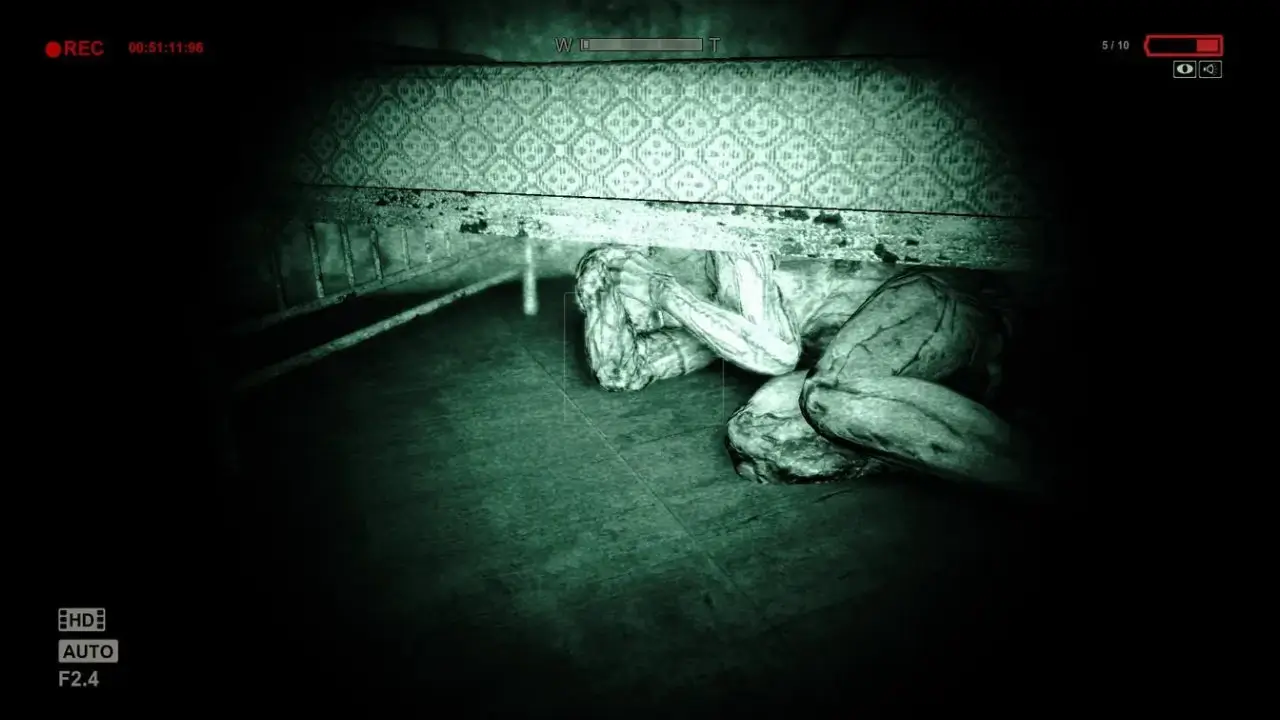

After Limbo’s significant success, Playdead started working on a (kind of) sequel. They switched from their custom engine to Unity, but added their own rendering routines to create Inside’s signature look. This time, the game wasn’t exclusively monochrome, and the environment wasn’t just a simple 2D platform. However, the art style and atmosphere still treat players to another unique experience. The main character is once again a boy in a dark environment (once again) full of hostile creatures and mechanical and environmental puzzles.

If this sounds a lot like Limbo, well, it is – but in my opinion, this similarity isn’t a downside. The game’s ending is, like the first time, open to interpretation (and there are lots of them out on the internet). In my opinion, it completely fits the game’s general atmosphere (although, this time there are two endings).

Inside the Limbo

After “Inside” came out (and achieved considerable success in sales), Playdead hasn’t published any other games. Checking their site recently, I saw that they’re hiring people left and right, and made a promising statement in their introductory text for open positions: “Our current project is a 3rd-person science fiction adventure set in a remote corner of the universe.” I’m a pessimist by nature and generally don’t trust people, but Playdead’s new title – I’ll buy it blindly, without question, remorse, or regret.

- Image credits: Playdead.

- References: IGN – “Limbo Review“.